The Resilience and Resistance Tale of George Takei, and the Takei Family

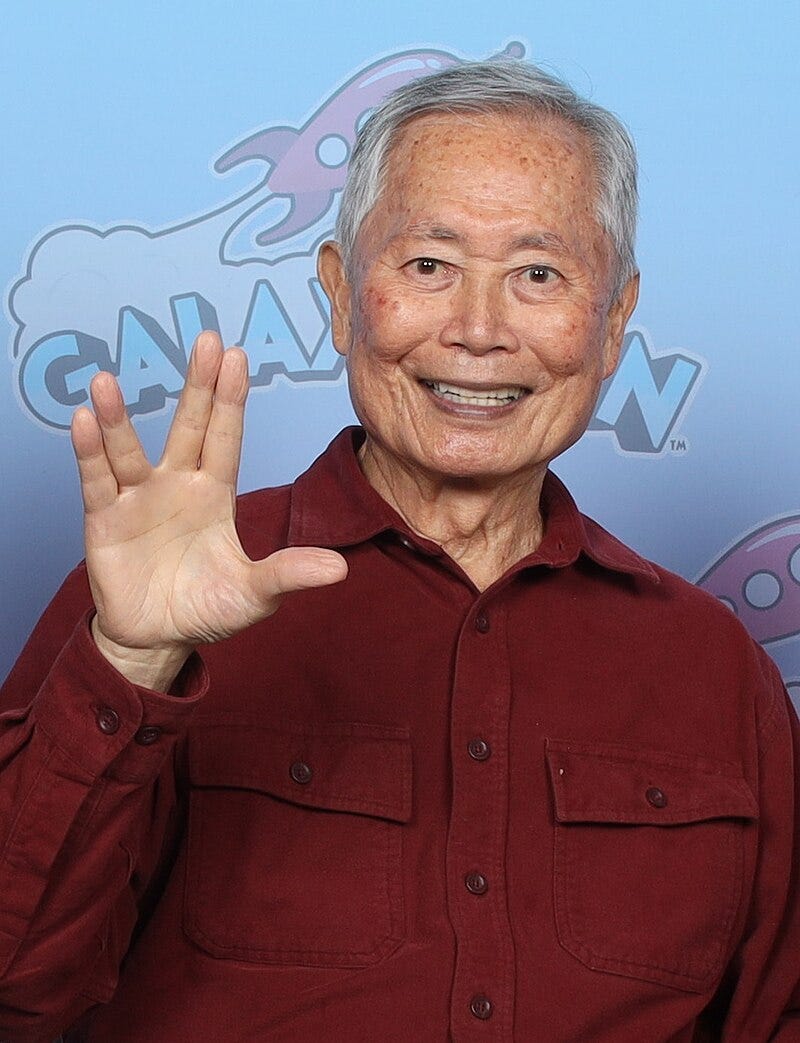

George Takei: World-famous Star Trek actor (helmsman of the USS Enterprise); author; producer; and social justice, civil rights & human rights advocate and activist (April 20, 1937-Present)

Once upon a time, in a place called Los Angeles, a young man with the last name, Takei, met a young woman with the last name, Nakamura. The man had lived in California since immigrating from Japan at the age of twelve; the woman was born in Sacramento, and had been educated several years in Japan. The two fell in love, and in 1935, wed.

On April 20, 1937, the couple bore a child. Reflecting the young man’s fascination with English history and culture, they named him “George” after the soon-to-be crowned King George VI, of England. A year later, George’s parents welcomed their second son, Henry, a roly-poly baby playfully named for the notoriously insatiable English King Henry VIII. In another two years, they welcomed to the world George’s sister, Nancy Reiko, called Nancy after a beloved family friend, and Reiko, or “gracious child” in Japanese.

A 1922 racist decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in effect for approximately thirty years prevented George’s father from becoming a naturalized American citizen, and discrimination, exclusion, and racism negatively impacted many aspects of his and other Japanese Americans’ lives. Nonetheless, George’s father held fast to the promise of American democracy and his vision of the American dream, opening a dry cleaning business, which prospered. For the first few years of George’s life, the family lived happily in a two-bedroom home in L.A.

They did, until shortly after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, when the lives of George, his family, and Japanese Americans across the West Coast drastically changed. Across America and particularly in California, bigotry, anger, and fear of Japanese Americans quickly reached a fever pitch. In California, the terrible sentiment to “Lock up the Japs!” came to represent the most popular political position in the state.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed and issued Executive Order (E.O.) 9066 authorizing the U.S. military to declare areas “from which any or all persons may be excluded,” and provide “transportation, food, shelter, and other accommodations” to persons excluded from those areas.

Two days later, California’s then-Attorney General, Earl Warren, determined to ride the tide of this sort of “populism” to become California’s 30th governor (which he did; and eleven years later, was even appointed Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court), and testified before Congress.

Warren urged the president, the War Department, and Congress, to use E.O. 9066 to carry out the mass military evacuation and exclusion of all persons of Japanese origin from all of California and the western halves of Arizona, Oregon, and Washington, without trial or hearing, as a “measure of national security and military necessity.”

In his statement and testimony to Congress, Warren leaned on racist tropes about Japanese Americans and advanced the argument that the FBI’s and U.S. military authorities’ absence of any reports of spying, sabotage, or other illegal or suspicious activities by Japanese Americans, should not allay fears about their loyalty to the U.S.

Rather, he cited this as the “most ominous sign in our whole situation” designed to lull American lawmakers and enforcers into a “false sense of insecurity.”

Soon after, official plans and actions to carry out Warren’s recommendation were launched across California and all along the West Coast. Over a hundred civilian exclusion orders were issued, each ordering Japanese Americans to report to a designated landmark for processing and removal. The U.S. government also seized the financial assets, property, and businesses of nearly all Japanese Americans.

And so, in May 1942, three weeks after George’s fifth birthday, U.S. soldiers arrived at his family’s home and ordered them to leave. His family was brought to the Santa Anita racetrack and given as shelter, a horse stall, an unsanitary space reeking of manure. George’s sister got sick first, then he did. Their mother cared for them as best she could. George and his sister recovered. In time, George had some semblance of normalcy when he started attending kindergarten beneath the Santa Anita grandstand.

Several months later, the U.S. War Relocation Authority ordered George’s family to relocate to another internment camp, far away, in an Arkansas swamp. On the long train ride, George’s father told him they were going on a “long vacation.” His Mom did her best to distract George and his siblings and ply them with treats. Thanks to his age, resilience, and his parents’ brave determination to appear cheerful and calm despite the terror and anxiety they felt, George viewed the trip as an adventure.

In Arkansas, George and his family lived in a cabin inside the barbed-wire prison that was Camp Rohwer, and would serve as their residence for the next 1 1/2 years. When they arrived, the cabin was steaming hot, and bare, but his father opened the windows and fetched army cots, and his mother went to work with a sewing machine she had smuggled over the journey. She wasted no time in fashioning curtains, rugs, and clothes from Army surplus fabrics and strips, in a creative and courageous effort to transform their empty cabin into something resembling a home.

Meanwhile, George’s father threw himself into efforts to help other families living in their block, becoming block leader and using his fluency in English and Japanese to represent the community’s concerns. In an interview conducted close to his eighty-seventh birthday, George said, of his parents’ determined efforts to help him and his siblings feel safe, and his Dad’s unrelenting activity in furtherance of new and creative ways to make life for the community of those interned in the camp with them, more bearable, and even, as much as could be managed, fun:

He was [always] setting up dances for teenagers or building baseball diamonds or helping old folks. I really think my father was Superman to have done what he did in camp and still be our father. I feel very blessed having the parents I had. We lived through so many scary, terrifying events...As long as we were with our parents, we were safe. My parents defined who I became—they and all the stresses we went through made me who I am today.

In January 1943, after the U.S. War Department issued a mandatory Loyalty Questionnaire for all imprisoned Japanese adults' completion, George’s parents faced a dilemma. While the war authority clearly wanted them to answer “yes” with regard to two questions, they decided they must answer “no,” as answering “yes” would put them in a false position. It would also send George’s father away from his wife and children, leaving them unprotected; and sending him into perilous combat for a country which had imprisoned them, labeled them “alien enemies,” and stripped them of everything they owned; and this, George’s father could and would not stand.

For answering “No” to these questions, George’s parents were branded “disloyals” by the War Department and, in May 1944, relocated again to the notorious Tule Lake Camp, to live among other so-called “disloyals” behind three layers of barbed-wire fence, where they were guarded and policed by battle-ready troops in machine-gun towers. In Tule Lake Camp, life became increasingly dangerous, as unjust imprisonment and harsh military rule increasingly radicalized certain young men, leading to crack downs and raids of suspected radicals, with innocent people often arrested; and tensions increasing between internees and guards.

For George, however, the camp offered certain compensations. His family’s quarters lay just across from the mess hall; and it was in the mess hall where, on movie nights, films were shown. This allowed him to dash over on movie nights to nab front-row seats. On movie nights, through American and Japanese film, George was transported far from the barbed-wire enclosed camp in which he and his family were imprisoned, into a magical world of people he’d never imagined, in places far away. He found both a revelation, including the world of silent Japanese film to which a member of their community, designated the benshi, provided the sound track.

In August 1945, the U.S. bombed the Japanese cities of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, resulting in devastation and unprecedented, horrific deaths from atomic weapons; after which the Japanese government soon surrendered. At the war’s end, the U.S. decided that George’s family, along with other interned Japanese Americans, was finally due for release, and provided them a meager twenty-five dollars each and a one-way ticket anywhere in the U.S. While fearful of the racism and hatred they had experienced in L.A. at the start of the war, George’s father and his family nonetheless chose to return, and seek to re-establish their life there.

For George and his family, life continued to be difficult, scary, and treacherous in their first few years in post-war L.A. Impoverished and unable to find other housing or significant employment due to discrimination, they lived these years in high-crime Skid Row. For lack of other available paid work, George’s father worked during the day as a dishwasher and, for a time, opened a small employment agency to try to help other Japanese Americans get back on their feet, for free.

In 1950, George’s father started a new dry cleaning business and moved his family to a Mexican American neighborhood in East L.A. There, George and his family found their Mexican American neighbors and community warm and welcoming, and they thrived. George took Spanish throughout junior high and high school, engaged in leadership activities, and graduated with honors. His father got involved in politics and activism in their community, and remained active in both until his death in 1979.

As George grew into adulthood, he followed his Dad’s example, becoming active in politics, and in many civil rights and social justice causes…

As a theater student at UCLA, George got to meet the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. After this meeting, George and his cast mates sang at civil rights rallies, and marched with Dr. King.

In 1964, at the age of 27, after struggling some years to get acting work, George got his big break. He was cast in the role of Lieutenant Hikaru Kato Sulu, a “pan-Asian” officer in a new sci-fi TV series called Star Trek, a show featuring a singularly diverse cast and crew of space explorers engaged in a peaceable mission of seeking out new life, and new civilizations. Star Trek ran for three seasons, between September 1966 and June 1969. In syndication, it became more popular and developed a cult following. With the subsequent Star Trek film franchise, many TV spin-off series, and countless adaptions across various media, original cast members, including George Takei, became nothing less than legendary, intergalactic superstars.

Throughout his life, George Takei has sought to use his soaring profile as a celebrity to make as large a difference in social justice, civil rights, and humanist causes as possible. In 1981, George testified at a congressional hearing to urge the passage of legislation to provide restitution and a formal apology to surviving Japanese Americans unjustly incarcerated during WWII; legislation which finally came to fruition with the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. Since that time, George has been active in the cause to secure reparations for the descendants of enslaved people in the U.S., and in causes related to rights and protections for immigrants; racial, religious, and ethnic minorities; and LGBT+ persons. He has also sought to educate a vast audience of people about his family’s experience of forced removal and internment, through appearances at many U.S. schools and universities, televised and podcasted talks and interviews, social media, a musical called Allegiance he produced, in which he also acted; and graphic novels targeting adolescents and teenagers, including They Called us Enemy, first published in 2019.

On March 12, 2017, an exhibit called “New Frontiers: The Many Worlds of George Takei,” honoring George’s life, career, and civil rights activism, opened at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, featuring many treasures and artifacts from George’s life and career. Chief among them was a tree root captured and sculpted by George’s father long ago, from the time of his incarceration in the swamps of Camp Rohwer, which his Dad had preserved, treasured, and saved across the family’s subsequent relocation to the camp at Lake Tule, as well as through his and his family’s later moves, to the end of his life.

For George Takei, his father’s ability to spot and find in the swamps of that internment camp, a thing of beauty embodied in the root of a cypress tree, worthy of capturing, sculpting, preserving, and treasuring throughout the time of their imprisonment, across many hardships thereafter, and over the rest of his life, is emblematic of his father’s teachings on the resilience required to live through, and somehow make life not merely bearable, but even beautiful and joyful, in harsh and terrible times.

In an excerpt from an interview published on October 16, 2020, George said:

This is part of resilience. You can’t just be moping and wallowing in your misery, in your pain. You have a right to it because you are in a horrible situation, but you can’t remain in that. You’ve got to make your joy, find your beauty.

Six days after his eighty-seventh birthday, George Takei’s publisher released his wonderfully narrated and beautifully illustrated children’s book, My Lost Freedom: A Japanese American World War II Story, to teach people of different ages and generations the lesson of his family’s and so many other Japanese Americans’ suffering and incarceration resulting from the misuse of the Alien Enemies Act and E.O. 9066; multiple leadership failures on the part of the U.S. government; and from the mass hysteria, racism, and anti-Asian and anti-immigrant sentiment that overwhelmed America during the second world war.

While promoting this book, and repeatedly over the past year, George Takei has warned that if Americans do not wish to repeat the irreversible mistake our country made in unjustly incarcerating some 120,00 Japanese Americans during WWII, stripping them of their liberty, property, and most fundamental rights, we must learn to read and understand our history, at its darkest as well as its brightest moments; and recognize that our “people’s republic” and democracy is very fragile, relying on citizens’ vigilant, frequent, and conscientious exercise of our participatory democratic rights in an effort safeguard civil liberties for all.

He has urged that when our democratic institutions, fundamental freedoms, and vulnerable populations are under threat, we must be prepared to demonstrate resilience; exercise true leadership and activism; and raise our voices in defense of our institutions, civil liberties, and social justice for those other than ourselves.

Excellent, Lois. I am glad to learn these details. Unjust and unacceptable racist treatment of a group of citizens based on social and political fear. All those interned in the camps showed more patriotism than those who put them there. We have a lot to learn from them.

I loved this. George and his activism are a constant reminder that we can come back from anything with courage and compassion.